| The Greek Civil War, 1944-1949 By Tom Cooper, with additional details by Nicholas Tselepidis Oct 26, 2003, 14:11 |

|

In April 1941, Germany invaded Greece and occupied it in a typical „Blitzkrieg“ campaign, that defeated not only the stubborn Greek but also the resistance of British troops deployed in the country, forcing the King George II and his government into exile in Egypt. Aside from the government, also a sizeable part of the Greek military managed to escape the German onslaught, including most of the (then) Royal Hellenic Navy, several thousands of Army troops (which later formed the “Greek Sacred Regiment” and the “Rimini Brigade” as well as a better part of the Royal Hellenic Air Force (RHAF). The later included most of the “Sholi Ikaron” – the RHAF Academy – with many pilots and technicians who were veterans of fighting Italians on the Albanian front. This personnel was used to form three RAF “Greek” Squadrons: No.13, 335 and 336.

The Greek Communist Party (KKE), led by George Siantos, became the core of the resistance movement and established a broad front organization – Ethinikon Apeleftherotikon Metopan (EAM – National Liberation Front), which raised a Liberation Army (ELAS). While ostensibly independent from KKE, the EAM was, in fact, tightly controlled by the Communists. Simultaneously, Army officers loyal to the King organized the other core, named Ethnikos Dimokratikos Ellinikos Syndesmos (EDES – National Republican Greek League), under Nikolaos Plastrias and Napoleon Zervas. Politics played a main role in relationship between ELAS and EDES very early, and was precursor of what was to follow. Even if ELAS tended to be somewhat independent, preferring to defeat the Germans first and talk about politics later, a bitter confrontation developed between the EAM and EDES. Of course, with the time the Communists made sure that ELAS toed the party line more closely.

Other groups to the right developed as well, foremost the organization named “Kh” (or X), commanded by the Cypriot-born Col. George Grivas, which waged a war of terror and counter-terror against the EAM and ELAS and their sympathisers. In this cauldron of extremes, the more moderate anti-Communist organisations quickly became irrelevant and ineffective.

At the time Greece had very poor communications: there were hardly any paved roads and the only main-line railway ran north from the Peloponnesus through Athens to Thessalonica, after which it branched to former Yugoslavia, Bulgaria and Turkey. This rail line was an important means of supply for German forces in Crete and even North Africa during the WWII. Almost the whole of its length was vulnerable to sabotage: during the WWII, British demolition squads, assisted by ELAS guerrillas, twice dynamited one of the three viaducts south of Lamia, which were guarded by Italian troops, putting the line out of use for months. Most serious attack was the one against the Gorgopotamus rail bridge, undertaken in a joint ELAS-EDES operation led by British Colonel Meyers, on 25 November 1942. Unfortunately, this type of cooperation did not last long as political objectives of the two Greek fractions were very different.

For years, the Germans were concerned that Greece might become the place where the Allies would open their “2nd Front” – i.e. invade the European continent. For this reason the German Wehrmacht held considerable assets stationed in the area. This changed after massive defeats on the Eastern Front, in 1944, and even more so after the Allied landings in France. Subsequently, the Germans began a withdrawal of their units from the Balkans, where these were threatened to become cut off and isolated by swift Soviet advance through the Ukraine and Romania, in the second half of that year.

Towards the end of the occupation, ELAS began to form regular units and its commander, Stephanos Saraphis, prepared to take over the country. Already in 1944 Churchill and Stalin had agreed that Greece should come within the British sphere of influence, however, and ELAS never won Western support. On the contrary, while the royalist and nationalist groups were preparing the return of the exiled King from Cairo, the British were keen to bring the country under their control as soon as possible.

On 17 September 1944, two British brigades and some Freek Greek troops, about 26.000 troops in all, under command of Lt.Gen. C.J. Scobie, landed in Greece to liberate it from Germans. Although their advance was swift, and by 23rd of that month Araxos airfield had been captured, while Athens and the surrounding airfields were taken by mid-October, after a paradrop on Megara airfield, Germans proved to be only the beginning of the problem. Greece had been devastated by the war. Thousands of civilians had been uprooted. The country was economically bankrupt – industry was at a standstill, factories destroyed, ports and cities in ruins. The civil government was in chaos, almost ineffectual in dealing with the country’s problems.

Scobie could do little more than occupy the major towns while the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) began the immense task of getting the civilian population back on its feet. In the following days the British – who were welcomed by the Greek population – begun ferrying in supplies with Dakota transports, while Supermarine Spitfires of Nos. 32 and 94 Squadrons RAF, DeHavilland Beaufighters of 108 Squadron and Vickers Wellingtons of 221 Squadron were all deployed to Kalamaki airfield – re-named Hassani, from 1 December 1944 (later to become known as Hellinikon) – outside Athens. By November the RAF was reinforced by two squadrons of Wellington bombers and also two RAF “Greek” units of Supermarine Spitfire Mk.VB/VCs, the No.335 and No.336 Squadrons. The designations of the two later units were to form the basis for the designations of all subsequent Greek Air Force units. Also to arrive back in Greece was the No.13 Squadron RHAF, equipped with Wellington Mk.XIIIs. Finally, during September 1945, the RAF deployed three units equipped with Douglas Boston Mk.V bombers in Greece, as follows:

- No.13 Squadron (arriving on 12 September 1945, and remaining in Greece until its disbandment, on 19 April 1946)

- No.18 Squadron (arriving in September 1945, and remaining in Greece until its disbandment, on 31 March 1946)

- No.55 Squadron (arriving in September 1945, and remaining in Greece until 1st November or December 1946).

These units were all based at Hasani airfield, and the No.55 Squadron has had few Mosquito XXVIs in service as well.

By the time the British and Free Greek troops arrived, the Communist guerrillas had begun to consolidate control of the countryside, with the main objective of undermining and destroying the Greek internal security battalions, the gendarmerie. The ELAS was relatively well organized and – trained, as it used German, Italian, British, Australian and New Zealand soldiers, deserters from various armies that were n Greece, as instructors.

ELAS had been offered a limited role in the post-war government, but dissatisfaction with this arrangement resulted in demonstrations in Athens. With the Greek government unable to control a deteriorating situation, fighting between the two main enemies, the EAM and EDES, began in Athens on 2 December 1944, when at one banned meeting British troops opened fire and around a dozen of demonstrators were killed. On the following day open hostilities between EAM and EDES began, with EAM artillery hitting British headquarters with its first shots. A Communist secret police force, named OPLA, fanned out into the city, knocking on doors and killing thousands of real and suspected enemies of the party. In three weeks, OPLA executed an estimated 13.500 Greeks – twice the number of their own countrymen killed during the three years of German occupation.

Meanwhile, on 4 December, police stations were attacked and RAF aircraft at Hassani began flying attack sorties against ELAS and EAM targets, mainly in the Athens area. From 9th of the month the RAF units at Hassani were reinforced by Spitfire-pilots of the No.40 Squadron as well as Dakotas of No.44 Squadron South African Air Force (SAAF). Together with Bostons of No.13, 18, and 55 Squadrons, all RAF combat aircraft played an active role in the followign campaign.

The effectiveness of British (and South African) air attacks was limited and on 15 December a flight of six rocket-equipped Beaufighters of No.39 Squadron RAF was attached to the 108 Squadron. According to most reliable accounts, the EAM and ELAS units had about 40.000 men and women organized into two “armies”: Army South, commanded by Siantos and Mandakas, about 18.000 combatants in three divisions; and Army North, commanded by Saraphis and aris, about 23.000 combatants in five divisions. These now attempted to take Athens, and on 19 December AHQ Greece, at Kifisia, was attacked by guerrilla. After a spirited defence by No.2933 Squadron RAF, it was overrun the next day: many British prisoners were taken and marched north.

Undermanned and outgunned, the British – encouraged by surprise Christmas Day visit to Athens by Winston Churchill, reacted in force, deploying rocket-equipped Beaufighters to strike a number of targets: In just two weeks No.39 Squadron flew sorties against 105 targets, including two radio stations, seven gun emplacements, 19 different Headquarters, 55 buildings, and ten ammunition and fuel dumps. Simultaneously, the No.108 Squadron flew 244 day- and 21-night sorties, while Wellingtons of No.221 Squadron were involved in supplying the No.32 Squadron at Sedes, dropping flares in support of night attacks, and leaflet raids. On two nights the Wellingtons also bombed different targets, using 250lb and 500lb bombs, all with delayed fuses.

Although EAM/ELAS had driven Zervas and his EDES off the mainland to the island of Corfu, the British Army proved too much for the guerrilla: by 7 January 1945 Athens was back under British control, with ELAS fleeing 150 kilometres north. Foolishly, the Communists refused to release about 16.000 civilian hostages they had rounded up, a strategy that greatly reduced ELAS’s popularity in the countryside and allowed the government forces to regain large areas. A ceasefire was announced on 11 January and the communists forced to accept terms, signed as the “Varkiza Agreement”. EAM broke up as a front organization and ELAS was destroyed as a fighting force. Thousands surrendered but a few hard-core elements took to the hills. Besides, the cease-fire did not prevent the deaths of 25.000 Greeks in what later became known as the first phase of the Greek Civil War.

In return, the RAF units in Greece lost a number of aircraft during this period, all in different accidents. A Baltimore V (FW808) crashed on landing in Hassani, on 25 December 1945; a Marauder III (HD627) stalled and crashed near Hassani on 24 June 1945, and another Baltimore V (FW798) collided with Liberator (KL380), also at Hassani, on 11 September 1945. It remains unknown how many crewmembers were killed.

With promises of government reforms, many of the Communist groups disbanded, and ELAS even surrendered a large quantity of arms. Many Communists, however, refused to disarm and took off to the hills. Some fled across the borders of neighbouring countries, vowing to return. For a few months at least, the situation looked better.

In the event, unkept promises led to continuing fighting through 1945, as hard-core Communists were determined to control the country, and their activities combined with an atmosphere of mutual distrust and hatred. They reorganized the scattered insurgents into a secret army, which filtered across the border to Yugoslavia and Albania, and established training camps. At the same time, government policies remained short-sighted: for example, the government allowed paramilitary terrorist units such as Grivas’ X Group to “clean up” ELAS elements in the cities in such a ruthless manner that thousands joined the rebel army. All such factors contributed to undermining and eventually breaking down the truce.

The British were now withdrawing their units from Greece. Most of RAF fighter units were out of the country by the early summer, being partially replaced by “Greek” RAF units, before three British light bomber squadrons, Nos. 13, 18 and 55 – were flown into Hassani, in September. The Greek RAF squadrons formally transferred to the Royal Hellenic Air Force (RHAF) only in mid-1946, but by the end of that year all RAF units had gone.

In the same year the RHAF was reinforced by formation of a third Spitfire-unit, the No. 337 Squadron: all three units now flew Spitfire Mk.IXs. A number of Spitfire LF/HFs was delivered as well, with most of the later being modified into LFs. A number of Spitfire Mk.XVIs was delivered from 1949 as well. Meanwhile, already in 1945 the No.355 Transport Squadron was formed and supplied with various transports, including Douglas C-47 Dakotas/Skytrains, Avro Anson Mk.Is, Vickers Wellington Mk.XIIIs, and Airspeed AS.10 Oxfords, while the Nos. 345, 346 and 347 Tactical Reconnaissance Flights were equipped with North American T-6/Harvard Mk.IIA/Bs and Taylorcraft Auster AOP Mk.3s. These aircraft were mainly based at Sedes, Larissa, and Elevsis, but time and again also at Yannina and Kozani.

Yugoslavia, Albania and Bulgaria all supplied arms and some materiel aid to the rebels, who were permitted to establish a “model community” based on the purist Stalinist orthodoxy, near Belgrade. But, from Stalin, who had the most to gain from the situation, came nothing except exhortations in the United Nations. At a meeting of the UN Security Council, on 21 January 1946, for example, the Soviet Union representatives loudly condemned what they called the persecutions of leftists in Greece, and the Greek Communists saw this as a sign that the USSR would not support a new armed rebellion.

Meanwhile, the Communist Party of Greece was divided between counsels of a political struggle or a continuation of the armed uprising, but the Siantos’ view prevailed and the party agreed to operate legally in Greek politics. It chose, however, to boycott the March 1946 elections: late that month, small ELAS units under the command of Gen. Markos Vaphiadis, entered the village of Litochoron and attacked an army platoon, which quickly surrendered. Some gendarmerie in a police station put up a stiffer resistance, but soon they put up a white flag too. The insurgents then retreated without a scratch as a British unit approached. Few months later, a band of between 1.000 and 1.500 men attacked and overran a gendarmerie post in the town of Deskati in Thessaly. Villagers later said the rebels looked ragged, almost starved, but that they were armed with 3-in mortars and PIAT anti-tank weapons. The garrison was betrayed by a second lieutenant who led 20 gendarmes over to the rebel side. It took government forces five days to clear the area and restore order, with the rebels retreating across the frontier into Yugoslavia – the last stages of their retreat covered by fire from that country’s armed forces.

In September 1946, King George returned to Greece after a plebiscite had decided in his favour. But, by the time the revel units were making almost daily forays over the border: roads were mined and villages burned, the marauders passing without hindrance over the frontiers from the neighbouring Communist countries. The stage was now set for the main civil war between the KKE and the Greek government, between the communists and the nationalists.

The major difference from the previous period was that the KKE’s support and training bases were now over the border, in the new communist states of (former) Yugoslavia and Albania, which were to be a complete sanctuary. A “Democratic Army of Greece” (DSE) was established under Gen. Vaphiadis, probably the best of the communist generals, who was a firm believer in guerrilla warfare and the gradual wearing down of the Greek government. Markos was a member of the Greek Communist Party already since 1938, and served as political commissary of the ELAS’ Macedonian group of divisions during the WWII, becoming the commander of the DSE in 1947. Under his leadership, the initially 11.000 strong DSE soon controlled much of rural Greece.

The years 1944-1946 were actually a build-up period for the communists, restricted to recruiting, obtaining supplies, sabotage of communications and general harassment by hit-and-run tactics, with emphasis on control of the frontier area, especially the corner nearest Lake Prespa. Nevertheless, activity was spread throughout the country, down to the Peloponnesus Peninsula. The communists had to adopt a totally different attitude to the villages, compared to previous times. Earlier on, the villagers had been the main source of support, supply and recruits for ELAS, but afterwards this was markedly less so. Most recruits during the civil war were young men and women, with idealist and left-wing views, mainly from the towns. During the WWII, the villagers were therefore ready to support ELAS on patriotic grounds against the German and Italian invaders. Being conservative and traditional in outlook, however, they were less ready to support a communist force against the constituted government. So it happened that while for ELAS villages were bases, for DSE these became military targets. In turn, this accounted for the fact that the DSE’s strength was never over 25.000: this lack of mass support was a critical element in the failure of the communists.

Early on, the main guerrilla offensive tactics was hit-and-run attacks on villages to capture arms and food, kill government sympathisers, abduct hostages and conscript recruits. The effect of this was to cause the government to spread its forces defensively throughout the country. Even some major assaults, with forces of more than 2.000, were made on frontier towns.

|

| Map of Greece, showing strongholds of the communist Democratic Army (DSE), in 1946 and 1947. (Map by Tom Cooper, based on Encarta 2003 software) |

The national government in Athens, meanwhile, dithered over the situation. Relying on right-wing groups to fight ELAS sympathisers in the cities, instead of sending out forces into the countryside, it could not show the rural population that the government was protecting them – even if the government depended on the tough, resilient peasants for its survival.

Under the influence of the British, the government also thought of the rebels in “bandit” terms, rather as guerrillas. This almost proved a fatal mistake: involved government forces – gendarmerie, national guard and police – totalled about 30.000 under-equipped, poorly trained, and poorly led men, who could not tackle “bandits”. It was not before October 1946, that the government finally began committing units of the newly-formed 100.000-man Greek National Army (GNA): this was now almost exclusively equipped by the British, however, it was neither trained, armed or organized for counterinsurgency operations. Without surprise, its first offensive, code-named “Terminus” and launched in April 1947, saw only few cordon operations in the Pindus Mountains and was unsuccessful.

Vafiadis meanwhile re-organized his force of about 4.000 fighters into semi-autonomous units of 10 combatants each. By the end of 1946, he had already 7.000 fighters in the DSE, and could establish his headquarters inside Greece, at the juncture of the Albanian, Yugoslav and Greek borders, in the rugged terrain of the Grammos and Vitsi Mountains.

By early 1947, the DSE was controlling perhaps 100 villages in Greece: the Communists conscripted the able-bodied, commandeered supplies and levied taxes. Thousands of real and imagined government sympathisers were shot after show-trials that entire villages were compelled to attend. Nevertheless, by March 1947, the DSE had 13.000 fighters in organized units, with the active support of perhaps as many as 50.00 others in the villages and towns.

Meanwhile, there were several secret Communist organisations carrying out assassinations and terrorism in the cities. By mid-1947, Communist rebel forces had grown to 23.000 active in the field – about 60 to 70 battalions, each composed of about 250 men and women. According to Greek government figures, in October 1947 alone, the DSE had attacked and pillaged 83 villages, destroyed 218 buildings, blown up 34 bridges and wrecked eleven trains. More than 250.000 civilians had been made homeless by the war, and four-fifths of Greece was insecure to government forces.

The Greek government was now in desperate position: the Communists were in complete control of the Mourgna massif, the range of highlands that stretches for 20 miles along the border between Greece and Albania. They also controlled the Grammos Mountains at the northern end of the Pindos range. From these bases, they threatened the entire north-western Greece.

At the times of the WWII, the guerrillas’ weapons were mostly gleaned from the battlefields, and were therefore a mixture of Italian and British origin. When ELAS was defeated in 1945, it handed in over 40.000 rifles, 2.000 machine guns, 160 mortars and 100 pieces of artillery: most of these were old weapons, as captured German weapons were cached. Soviet supplies became available only at a later stage of the war, including rifles, mortars, flame-throwers, field guns up to 105mm and anti-aircraft guns. As a result, during the civil war there was a constant ammunition and re-supply problem. Some small naval craft were used round the coasts and even one old Italian submarine for the transport of supplies. The underground organization (YIAFAKA) was reported to be 50.000 strong, with 500.000 sympathisers.

Government forces totalled meanwhile about 180.000, but were deployed in small and scattered groups in defence of towns and villages. The GNA was static because the politicians refused to allow units to be moved from their own local sphere of interest. More than 700.000 people fled as refugees from the rural areas to the towns and the situation rapidly deteriorated without any major battles taking place. In the words of GNA General Papagos: “The national forces were in danger of losing the war without fighting it.”

In March 1947, the government appealed to the United States and President Harry S. Truman. Greek emissaries went before the US Congress and asked for $400 million in aid for Greece and Turkey, Gen. Papagos stating: “It must be the policy of the United States to support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures.” On 12 March 1947, President Truman announced the “Truman Doctrine”, aimed at preventing Soviet Union from gaining control of Greece and Turkey. The Doctrine stated that the United States would not allow aggression to be accomplished by pressure or by subterfuge. Later, in May, Truman would publicly state that the “national integrity and survival of Greece and Turkey were of importance to the security of the United States and of all freedom-loving people”.

At first, however, the actual intention of the Doctrine was puzzling to both Europeans and Americans alike: it was simply unclear what did it mean. When a Soviet representative on the United Nations Commission in Greece asked an American official what the Doctrine mean, the American replied, “It means you can’t do it.” The Russian smiled and said, “I quite understand.” The point had been made: the Doctrine simply meant “no”.

Within weeks, an American Military Advisory Group was established in Athens and by August 1947, US supplies and equipment had began to arrive, initially including a number of C-47s and T-6D/G Texans.

The arrival of the Americans caused the Communist Party to accelerate its own programme. On 24 December it decided to establish a “Free Democratic Greek Government”, and deployed a force of more than 2.000 fighters, supported by some artillery, in an attempt to capture Konitsa – required as a capital on Greek soil. The first objective was the bridge at Bourazani, which spanned the Aoos River. Along this route would come the government reinforcements from the provincial capital Yanina. But the townspeople of Konitsa fought the guerrillas desperately, turning their homes into forts and fighting alongside the government troops. More Army units were flown in by RHAF C-47s and DC-3s commandeered from civilian airlines. From Christmas Day 1947 to New Year’s Eve, the battle raged on. Finally, it was too much for the insurgents. Leaving behind some 1.200 casualties, they simply melted away across the frontier.

The assault on Konitsa failed, just like the previous on Florina. Yet, another intended effect of all these attacks was to create more than 700.000 refugees who fled into the coastal area where they stretched government resources.

Reinforced by US aid, and in high spirits after the defence of Konitsa, in 1948 the GNA – now US-equipped and –advised force of some 200.000 troops in eight infantry divisions and three independent brigades, supported by artillery, armour and aircraft - went over to the offensive. In March the RHAF identified and attacked two guerrilla landing strips near Lake Prespa. These had been presumably prepared to receive supplies and men from Albania and Yugoslavia. It must be said, however, that neither country is known to have operated any kind of transport – or other – aircraft in support of the DSE. Quite on the contrary, the communist neighbours restrained from such actions for fear of provoking greater US aid or even an intervention. In turn, for fear that these communist countries might intervene on behalf of the DSE, the Greek government neither crossed the border nor retaliated. Also, in accordance with its agreement with the British, even the Soviet Union failed to recognise the new communist government, and supplied no aid.

In April 1948, the GNA launched the operation code-named “Dawn”, attempting to destroy the ELAS base areas in the Grammos and Vitsi mountains, but with only temporary success. This was the first offensive undertaken with full support of the RHAF, which in May flew 370 offensive sorties of a total of 641. Dakotas of 355 Squadron were used for flying supplies and dropping leaflets, while Spitfires were used as fighter-bombers. The RHAF operations against northern guerrilla bases were hampered by the need to avoid creating international incidents through bombing or shelling neighbouring countries. Consequently, a five-mile limit south of the border was placed on all strikes. On the other side, the DSE’s air defences were considerable by the time: ten Spitfires were damaged and one shot down in April and May 1948. The DSE subsequently expanded its guerrilla activity into populated areas, murdering government sympathisers and kidnapping recruits, including over 10.000 children aged under ten, who were abducted across the border. Such abductions, however, condemned by the United Nations, lost the communists much sympathy around the world. The government was able to take harsher measures and pressure to make terms with the ELAS was reduced.

|

| A T-6D of the 345 Flight RHAF, as seen in 1949. 50 of these aircraft were delivered from the USA, and upgraded to T-6G standard. The RHAF made extensive use of Texans, arming them with machine-gun pods and light bombs. (Artwork by Tom Cooper) |

Realizing that there was no longer any way he could win, in May 1948, Markos broadcasted a call for a cease-fire over the rebel radio in Belgrade. But, Nikos Zachariades, the secretary general of the Greek Communist Party, and the real power behind the insurgent struggle, refused to given in. Instead, he ordered Markos to abandon guerrilla strategy and operate in conventional, small brigades of three or four battalions. Before Markos could reorganise his units accordingly, in June 1948, the GNA launched the Operation “Coronis”, with 40.000 troops attacking 8.000 guerrillas in the Grammos Mountains. Fighting continued into the summer along 2.500m high ridges stretching south from the Albanian border, in an area where there was not even a dirt track that could be used as a road.

On 15 July 1948, the GNA attacked the Grammos base again, concentrating 40.000 troops. To take a mountain called Kleftis, the GNA artillery poured 20.000 artillery shells onto the peak – which finally had to be taken in hand-to-hand fighting. The ground troops were again supported by 335 and 336 Squadrons, deployed up to Yannina and Kozani, together with several North American AT-6 Harvards. A flight of Harvards and AOP Austers each was forward deployed at Argos Orestikon, to act as artillery spotters, while a flight of Oxfords used for photo-reconnaissance was based at Sedes. The 8.000 DSE fighters, led by General Markos Vaphiadis personally, put up fierce resistance. When on the defensive in the mountains the guerrillas usually dispersed, escaped into Albania or Yugoslavia in the face of superior government forces and returned to the area after they had left. In this case, however, the DSE refined this tactic by making an initial stand, thereby inducing the government to deploy large forces in an attempt to encircle the area, and then, at the very last moment, Markos had called in another 4.000 guerrillas. Finally, sometimes in August, he broke out of the government’s trap, retreated and escaped across the borders, leaving his base through the last narrowing gap, carrying 3.000 wounded, but also some 3.000 dead.

In total, the RHAF flew 3.474 sorties during Operation Coronis: 23 Spitfires were damaged, but only one crashed, killing the pilot. By the time the third RHAF fighter unit, the 337 Squadron, became operational. The Spitfires lacked endurance and ammunition capacity, and proved vulnerable to ground fire. Besides, air strikes were hampered by poor ground-to-air communications and were either pre-planned or carried out in response to a call-up from observation aircraft, normally the AT-6s. The RAF still had to assist, deploying Mosquitoes of 13 Squadron for photo-reconnaissance, but the RHAF was already well underway to become completely independent from foreign aid at least in regards of training, then an Air Force Academy – the so-called “Scholi Icaron” – was re-established at Tatoi, equipped with Harvards and DeHavilland Tiger Moths.

The RHAF was meanwhile so much in need of bombers, that Col. Keladis, then the Commander-in-Chief of the air force, ordered a feasibility study and subsequent modification of three C-47s into bombers. “DAK-348” became the prototype for this conversion, undertaken by the workshops of the 202 KEA. Modified aircraft received external hardpoints, the main panel in the floor was removed and the structure around it reinforced. Finally, a bombsight was added, together with position for bombardier. The first flight test of aircraft in this configuration was undertaken at Hassani, on 14 August 1948, by Capt. Koskinas as pilot and Capt. Damaskinos as co-pilot. Already after the second test-flight the DAK-348 was sent to Kozani airfield, from where it flew bombing sorties for two days, before returning for inspection to Hassani, on 19 August.

Upon an additional test-flight, this “Dakota bomber” was deployed to Kozani again. Because of success of the conversion, Gen. Van Fleet subsequently approved similar modifications to be undertaken on a total of 15 C-47s. The rebuilding undertaken by 202 KEA was so successful, that Douglas later added technical orders and descriptions to the C-47-manuals, and corresponding modified Dakotas were later deployed as bombers in several other COIN wars. The 202 KEA continues to provide the Greek Air Force with invaluable maintenance services until today.

Not letting up the pressure, the Greek Army again went on the offensive, this time in the Vitsi Mountains area, where the GNA had partially encircled the elusive Markos and 13.000 guerrillas. the GNA launched an operation in the Vitsi area, again supported by the RHAF, whose Spitfires this time proved particularly effective even against well-camouflaged targets. Namely, the ground-to-air communications were significantly improved by the time: the troops on the ground were now able to request close support and the RHAF proved able to respond swiftly. The Spitfires were now equipped with napalm bombs, which were used extensively when RHAF fighters harried a group of guerrillas who had attacked the village of Edhessa. No less but 157 guerrilla were killed, while the rest was forced to spilt and make for the border. Then the Communists counterattacked and pushed the national troops back, but at a heavy price in casualties.

In total, the RHAF flew 8.907 combat sorties in 1948, and 9.891 transport sorties, losing 12 aircrew killed. The experience of Greek fliers was positive: although mountainous terrain favours hit-and-run guerrilla tactics, the government forces, making full use of air power, showed that guerrilla forces had to be wary of risking any confrontations, even in such seemingly unfavourable terrain. Many of the Greek mountain ranges rise to more than 1.500m, and some to over 2.700m. About 40% of the population at the time used to live in scattered villages in the mountain valleys where roads were poor – or non-existent. In the winter the mountains were made even more inaccessible by rain and snow. This was not, however, always to the advantage of the guerrillas, because government forces were better equipped and clad and could recover afterwards in warm barracks, whereas many guerrillas died of cold and exposure.

The GNA had to solve enormous problems in the mountains. Tanks and armoured vehicles could rarely be used, and although US aid included 8.000 trucks, 4.000 mules were found to be of more help. The guerrillas were irretrievably losing this last battle: they were fighting doggedly, but were basically involved in raiding against a better equipped enemy, who realised that a patient deployment of its overwhelming force would bring victory.

|

| The venerable Douglas C-47 Dakotas and Skytrains were delivered to Greece in considerable numbers. The example shown here is depicted as seen after the war, when "KN-575" was used as VIP-transport: this aircraft, however, is known to have been delivered to RHAF already during the Civil War in Greece. Its colours are essentially as it was delivered from the RAF, with white roof and aluminium on sides and underneath. A number of RHAF C-47s was modified as bombers in a manner that was later adopted by Douglas and introduced as "standard" for similar enterprises in other air forces as well. (Artwork by George Psarras) |

By the end of 1948 there were increasing differences within the communist leadership. General Markos, allegedly on grounds of ill health, was relieved of command and succeeded by Nikos Zachariades. Whereas Markos had favoured the continuation of political and guerrilla warfare, Zachariades preferred conventional warfare to defeat the Greek Army before its reorganisation and the build-up of US aid had become fully effective. As the differences between Markos and Zachariades widened, in January 1949, Zachariades replaced Markos as commander of the Democratic Army. Markos fled to Albania just ahead of Zachariades’ assassins. The strategy the later insisted upon was premature, however, and the DSE conversion into conventional brigades, divisions and corps simply presented the Greek Army with easier targets.

This change on the DSE’s top could not come at a better time – for the nationalist government, and resulted in dramatic changes. The communist hope of internationalising the war was in vain: intention of the Cominform – the international communist body, established by nine national communist parties – to create an independent Macedonian state rallied many nationalists and doubters to the Greek government’s side. Yugoslavia also “defected” from the communist bloc, and gradually deprived the DSE of its best outside supply and support. By July 1949, the Yugoslav border was closed to Greek communists.

The GNA cleared 4.000 rebels from the Peloponnesus, in January 1949, and the following month it was given a new commander-in-chief, the able General Alexander Papagos – hero of the 1940 triumph over the Italians, who accepted the post with the condition that the National Defence Council not interfere in military operations, and full powers to deploy the army as required.

Some causes of the communist defeat were therefore of their own making, but that should not detract from General Papagos’ brilliant campaign. Using the minimum forces to contain the communists in their mountain bases he concentrated first against the Peloponnesus. Just as important, he directed that the initial attack should be against YIAFAKA, in order to destroy its intelligence network and control over the population. All known communist sympathisers in the designated area were rounded up so that communist units were deprived of support and intelligence. The resistance was soon broken up: by early spring of 1949 the Peloponnesus had been cleared and by mid-summer the same tactics cleared the central Greece.

In response, already the first “conventional” DSE operation proved a costly failure: on 12 February two guerrilla divisions attacked Florina. The RHAF fought back despite bad weather, and was credited with having caused most of casualties among the 900 communists who were killed or captured.

The next rebel strike was on the village of Naousa, which was attacked in early June 1949. No less but 300 civilians were taken hostage, but RHAF Spitfires dive-bombed the retreating guerrillas in the Vermion mountains, forcing their release. This action eventually provoked a “final” GNA offensive, which in turn saw some of the bitterest fighting of the whole war.

The final GNA push against the guerrilla strongholds in the north began on 5 August 1949, and was code-named Operation “Torch”. Having feinted first against the Grammos base area, General Papagos launched a concentrated attack against the Vitsi base. The RHAF opened this attack by its largest strikes to date.

DSE’s General Nikhos Zachariades now made a crucial mistake: he deployed his forces, some 7.500 strong, in defence of their base in conventional tactics of positional war – admittedly in well-fortified positions with concrete emplacements and plenty of barbed wire – instead of withdrawing when faced with superior strength. This was a fatal error, then the GNA with its US-supplied firepower was too much for the DSE. This GNA offensive resulted in pitched battles along the long border with Albania, former Yugoslavia, and Bulgaria, which the Greek Army was previously unable to defend. Not this time: supported by over 150 combat sorties flown by RHAF fighter-bombers a day, the ground forces caused immense losses to the communists.

By the middle of the month Zachariades’ guerrillas were routed. A few remnants escaped through Albania to reinforce the Grammos base, which Papagos attacked in the second stage, beginning on 24 August. Here the RHAF deployed its newest acquisition for the first time: the 336 Squadron Royal Hellenic Air Force was meanwhile equipped with the first out of some 40 Curtis SB2C-5 Helldiver dive-bombers, obtained from surplus US Navy stocks. Helldivers played a major role in following operations, and they were used to great effect, dropping bombs and incendiaries on guerrilla hideouts.

By the end of the month it was all over. The RHAF flew 826 operational sorties, dropping 288 tons of bombs, firing 1.935 rockets and making 114 napalm strikes. As many passes into Albania were meanwhile blocked, the communists were completely defeated: wile some DSE guerrillas escaped to that country as well as to Bulgaria, their resistance was definitely broken. On 16 October 1949 a ceasefire was declared, ending the war. By that time the communists in Greece lost not only their military forces but also any claim to popular support in country. The Communist Party attempted to save face by announcing that it had ceased operations in order to preserve Greece from destruction. The war, however, left a bitter legacy from which the country began recovering only in the 1970s.

|

| Above and bellow: at least 41 Curtiss SB2C-5 Helldiver dive-bombers were delivered to RHAF from surplus USN stocks. The aircraft entered service with No.336 Squadron in early 1949, and thus saw only a relatively brief combat service. Nevertheless, it proved its worth beyond any doubt, by delivering precise and highly destructive attacks, especially as the DSE attempted to confron the Greek National Army in conventional manner. (Artwork by George Psarras) |

|

| |

In January 1951 the Greek General Staff weekly newspaper “Stratiotika” published a summary of losses suffered during the war. It gave Greek Army deaths at 12.777, with 37.732 wounded and 4.527 missing. It said a further 4.124 civilians and 165 priests had been executed by the communists. Deaths from land mines were said to be 931. Livestock lost included 114.754 cattle and 1.365.315 sheep, pigs and poultry. There were 476 road bridges and 439 railway bridges destroyed: 80 railway stations burned, 24.626 houses totally destroyed and a further 22.000 partly destroyed.

The Greek air force lost four or five aircraft – including at least one Spitfire – shot down by DSE, and up to a dozen machines to other reasons. Reportedly, a number of US pilots flew RHAF AT-6s during the war, and at least one of them should have been shot down, in January 1949. As a sign of Greek appreciation for US aid during this war, later on the RHAF was to deploy its No.13 Flight, equipped with C-47s, to Korea, to serve with UN forces, as part of the famous “Kyushu Gypsies”.

Estimates of the number of communists killed vary greatly, but 38.000 is considered a reliable figure: 40.000 were captured or surrendered.

Sadly, the lessons of this war were never properly learned in the West, nor even accurately interpreted. Military commanders came to think that insurgency conflicts could be won by conventional methods: by regular armies with increased firepower, while ignoring the fact that the Communists failed to establish an identity with the religious and conservative Greek people – especially in the rural area. Moreover, their brutal treatment of hostages and their unthinkable,, barbarous act of forcibly removing children were major and – in the end – irretrievable mistakes. Insufficient credit was also given to such tactics like temporary removing the civil population from the areas under guerrilla control.

Such and similar lessons have had to be learned again, in later wars.

In general, all RHAF aircraft from this period wore RAF-style camouflage patterns – mainly in “European” and “Desert” colours – and have had their national markings applied in all six spots. Once all the aircraft of RAF “Greek” units were officially transferred to the RHAF, their RAF codes, usually applied as large letters on the rear fuselage, were crudely overpainted. Some aircraft delivered at later stages of the war, like AT-6Ds, were still showing markings of their previous owners (blue flashes etc.), even if the RHAF personnel took some steps to remove a better part of these.

- Wellington Mk.XIII: A total of 12 Wellingtons were supplied to Greece from Great Britain. All used to serve with Nos. 38 and 221 Squadrons of the RAF Coastal Command, and were therefore delivered in their Coastal Command white finish, with faded Extra Dark Sea Grey/Dark Slate Grey upper surfaces.

- Spitfire Mk.VB/VC: A total of 56 Spitfire Mk.VBs and VCs were delivered to RAF “Greek” Squadrons starting from January 1944. They were officially handed over to the RHAF on 25 April 1946, and formed the core of the original RHAF fighting force deployed during the civil war, until replaced by later mark examples. Greek Mk.VBs and VCs remained in service until 1950. Most were painted bare metal overall, and had black anti-glare panels on forward fuselage: JK528, JK530, JK550 and JK809 were Mk.VCs and belonged to the original batch that entered service with No.335 Squadron, in 1944.

- Spitfire Mk.IX LF/HF: Deliveries of between 40 and 45 Sptifire Mk.IXs to Greece began in early 1947. These aircraft were mainly used for offensive reconnaissance, foremost by No.335 and No.337 Squadrons. All were painted in Ocean Grey/Dark Green over, Medium Sea Grey under, and wore black serials on rear fuselage, but their national markings varried in size from aircraft to aircraft considerably. From 1946 onwards, all have received large underwing serials, which "pushed" roundels towards the wingtips.

Mk.IXs delivered to Greece were:

- BS352, BS409, BS508, EN143, EN254, ER406, JL227, MA532, MA582, MA791, MH314, MH322, MH452, MH698, MK357, MK361, MK571, MK981, MK991, NH154, MJ292, MJ333, MJ474, MJ507, MJ839, PL356, PV119, PV193, PT492, PT604, PT660, PT943, TA823 and TA816.

- Spitfire Mk.XVI: The Spitfires Mk.XVI arrived in Greece in the early 1949, in sufficient numbers to equip all three fighter squadrons. Deployed intensively in combat, they retained the original RAF camouflage pattern in Ocean Grey/Dark Green over, Medium Sea Grey under. Black serials were applied on the rear fuselage: RW347, RW379, RW353, RW354, RW380, SL623, SL624, SL679, SL717, SL555, SL573, SL608, SL728, TA759, SM194, SM358, SM503, TB130, TB232, TB237, TB254, TB255, TB272, TB273, TB274, TB320, TB340, TB616, TB619, TB626, TB859, TB886, TB895, TB901, TB908, TD114, TD126, TD133, TD141, TD142, TD145, TD147, TD176, TD190, TD191, TD229, TD235, TD241, TD243, TD246, TD285, TD320, TD342, TD349, TD350, TD351, TD374, TD404, TE191, TE235, TE245, TE249, TE252, TE276, TE284, TE346, TE350, TE381, TE382, TE383, TE391, TE447, TE468.

- Spitfire Mk.PR.XIII: RHAF received only four aircraft of this type and almost nothing is known about their camouflage and markings - except their serials: EN656, MF190, MF466, and MF643.

- T-6D/G Texan/Harvard Mk.IIA/B & Mk.III: RHAF received a total of 25 Harvard Mk.IIA/Bs and 35 T-6Ds. Survivors were later modified to T-6G standard. Originally, all were left in bare metal overall, with yellow stripes on the upper surface of the wings. Harvards wore RAF-style serials on rear fuselage, like EX249, EX282, EX552, while T-6Ds wore serial numbers from 49-2722 thru 49-2756 on the fin. An AT-6C-NT Texan – serialled 32803 - can be seen on display at Polemiko Mouseio, in Athens, but this example probably belongs to a batch supplied after the war.

- C-47 Dakota/Skytrain: The original Dakotas supplied to Greece consisted of a mix of ex-RAF and ex-USAAF aircraft, and could be easily recognized by their serials (for example KK181 for ex-RAF, or 92637 for ex-USAAF). Most were left in natural metal overall, but some have got an overall camouflage of Olive Drab. The 30 ex-USAAF airframes were serialled 49-2612 thru 49-2641, applied in Black on fin, and all served with the 355 Squadron.

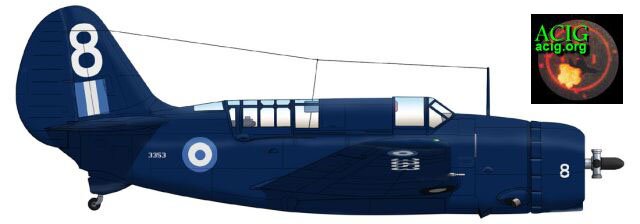

- SB2C-5 Helldiver: A total of at least 41 Helldivers was delivered to RHAF from mid-1949, and all served with the No.336 Squadron. All were painted in semi-gloss Sea Blue overall, and wore white serials on rear fuselage and under the wing. Some were seen also with single tail-numbers on the top of the fin and engine cowling:

- 2: 3480

- 6: 9386

- 8: 3353

- 9: 3329

- 10: 3719

- 11: 9250

- 15: 9193

- 17: 3350

Except for own research and materials kindly supplied by contributors on ACIG.org forum, including Mr. Sciacchetano Umberto, the following sources of reference were used:

- "AIR WARS AND AIRCRAFT; A Detailed Record of Air Combat, 1945 to the Present", by Victor Flintham, Arms and Armour Press, 1989

- “HELLENIC AEROPLANES, from 1912 until TODAY” (in Greek language), by G.C. Kondilakis, I.P. Korobilis, I.K. Daloumis, and M.P. Tsonos, IPMS of Greece, 1992 (ISBN: 960-220-336-0)

- C-47 DAKOTA IN THE GREEK CIVIL WAR (in Greek language) by L. Blaveris; War and History magazine

- IPMS-Hellas News: various volumes from 1990, 1991, 1992, and 1993.

0 comments:

Post a Comment